ARCHIVE

CHILD PRISONERS IN VICTORIAN TIMES AND THE HEROES OF CHANGE

In 1845 an eight-year-old boy was brought to trial at the August sessions in Clerkenwell near St.Pancras. His name was Thomas Miller and he had been caught ‘stealing boxes’. For this crime the boy was sentenced to a month in jail – and he was whipped.

In fairness it has to be said that in Victorian England there were only a few children under the age of 10 in prison, though the number of young criminals in jail aged more than 10 rises steeply. In the early years of the century all criminals were more or less thrown together in the common jail regardless of crime or age. But change was in the air and concern was rising over the rapid increase of petty crime. The first significant move came in 1823, when laws were introduced that provided separate lock-ups for those awaiting trial and the convicted and hardened criminals. Then it was recognized that a distinction should be made between the habitual and the casual criminal. Separate prisons were designated. We must assume that Thomas spent his month in the company of other casual criminals awaiting trial and not with the hardened convicts.

The punishment of transportation had been resumed by Act of Parliament in 1784, ‘to any place beyond the seas, either within or without the British dominions, as his Majesty might appoint’. Two years later an order was published fixing the eastern coast of Australia as the future penal colonies. The first band of transports left England for Botany Bay – and so the colony of New South Wales was founded. Within 50 years 100,000 had been transported to Australia – some 2000 a year.

Thomas was never sent to Australia. His sentence was commuted to 3 more months in prison. For the next four years he was in and out of prison, avoiding deportation twice and spending many months behind bars in the company of hardened criminals. The records lose sight of him after his conviction of June 1852, ‘when he was sentenced, under the Larceny Act, to be whipped and imprisoned 2 days. He is now only 12 years of age, and not more than 4 feet 2 inches in height.’

THE CURSE OF POVERTY

For the distance of time it is hard to imagine the state of London in the nineteenth century, before the motorcar or the railways, before the sewage system was built, before national health and guaranteed pensions, before the minimum wage. In 1872 Hippolyte Taine remarked that he recalled ‘the lanes which open off Oxford Street, stifling alleys thick with human effluvia, troops of pale children crouching on filthy staircases; the street benches at London Bridge where all night whole families huddle close, heads hanging, shaking with cold…abject, miserable poverty.’ Peter Ackroyd adds his comment: ‘In a city based upon money and power, those who are moneyless and powerless are peculiarly oppressed.’

It was the poverty, filth and squalour that drove many to crime – crime to brighten the darkness of life and to provide the means to survive. Many among the poor knew no other profession and the skills were handed down from father to son. And society responded with a severity that often failed to discern the root of the problem – locking away the luckless criminals or deporting them to a far away land.

A CELL WITHIN A CELL

John Garwood of the newly formed London City Mission, writing in 1853, expresses his distress over the number of children in jail: ‘The collecting of the prisoners for Divine service almost resembles the collecting of children to their school. This is undoubtedly the most affecting sight which a prison reveals. The writer has visited the prisoner awaiting execution, under sentence of death for murder, and he has visited the female wards of a prison. Both these are very pitiable sights to behold, but the swarms of juvenile prisoners are a still more pitiable sight.’

Captain Williams, Inspector of Prisons in the mid 1800s, told a select Committee of the House of Commons: ‘I do not know any fact that can strike any person more sadly than seeing a child under 9 or10 years of age in a prison. In conversing with this class, the feeling of pity increases… They are older when young than any other class.’ The number of sentences to imprisonment in England and Wales, under 17 years of age in 1849 was 10,460 of whom 214 were transported to Australia.

Lord Romilly, a distinguished reformer at the beginning of the 19th century, recorded his impressions of a visit to jail.

I had never before seen a dark cell, and therefore had no idea of the horrible place it was. A cell within a cell. The interior of the first is so black that when the governor entered it I speedily lost sight of him, and I was only made aware of his opening an inner door by hearing the key clicking in the lock.

"Come out here, lad," he exclaimed firmly, but kindly. The lad came out, looming like a small and ragged patch of twilight in utter blackness until he gradually appeared before us. He was not a big lad, not more than thirteen years old, I should say, with a short-cropped bullet-head, and with an old hard face with twice thirteen years of vice in it.

The prison dress consisted of a sort of blouse and trousers… he shambled out of the pitchy blackness at a snail’s pace, his white cotton braces trailing behind like a tail, and completing his goblin-like appearance.

FOR STEALING A PENNY TART

For the poor there was little mercy in the eyes of the law. Edward Joghill at the age of 10 had been convicted eight times and spent many days in prison. His crimes?

- Possession of 7 scarfs - 2 months

- Possession of a half sovereign - 1 month

- Simple larceny - 1 day's imprisonment and whipping

- Rogue and vagabond - 2 months

- Simple larceny - 1 month's imprisonment and whipping

Mr.Sergeant Adams stated before a Committee of the House of Commons that 30 to 40 children, of ages from 10 to 13, were often brought before him to be tried and sentenced at the Sessions; and that he had tried a child as young as 7 years of age, and a vast number of 8 and 9,sometimes for offences as small as stealing a penny tart.

‘Some years ago,’ he continued,‘I went over the Maidstone Gaol. I saw a little urchin about 10 years of age, and I said, "Who is that boy?" "Oh," said the Gaoler, "he has been committed by the County Magistrates for stealing damsons." He had got over a garden wall, and got a hatful of damsons and had been sent to prison for a month.’

Punishments were invariably harsh and not aimed at reforming the criminal or providing for their future. At the beginning of the century, children were punished in the same way as adults – sent to the same prisons, sometimes transported to Australia, whipped or sentenced to death. In 1814 five child criminals under the age of 14 were hanged at the Old Bailey, the youngest being only eight years old. Until 1808 pick-pocketing was punishable by death, along with 222 different crimes, from forgery to letter-stealing. William Potter was hanged in 1814 for ‘cutting down an orchard’.

Petty crime especially among children had increased sharply at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Looking for reasons is not simple, but the short answer has to be the increase in urban poverty, as a result of the growing industrial revolution that was turning British society on its head. In 1816 Parliament set up a committee ‘for investigating the alarming increase in juvenile crime in the metropolis (London)’.As people poured into the cities in the hope of finding work, so poverty increased and the slums proliferated. The Law was inadequate to deal with the new class of urban unemployed. Mass unemployment led to desperate poverty, overcrowding and squalour with the accompanying vices of crime, drink and prostitution. The children suffered through violence at home and poverty meant that many never went to school and took to the streets in gangs to engage in petty thievery and pickpocketing, the ‘prince of crimes’.

THE WINDS OF CHANGE

In 1832 the New Poor Law was introduced, providing facilities to deal with the problems of poverty. In principle the workhouses were not to provide much relief. ‘Those entering the workhouse would find life there harsh, monotonous and characterised by the intent of improving the inmate’s moral character.’

At the same time reformers began to look at the law, which up to that time had treated children as small adults – putting them in the same jails, judging them by the same harsh standards and punishing them with equal severity. Morality and child welfare entered the agenda both of Parliament and the conscience of the nation, stirred and eagerly promoted by a succession fine Christian reformers who made a lasting impression for good on society.

- Influential Quakers were behind the Report of the Committee for Investigating the Alarming Increases in Crime in the Metropolis, produced in 1816 and triggering a wave of reforms.

- Thomas Fowell Buxton, an evangelical Whig politician and member of that committee, campaigned successfully for an end to capital punishment for all crimes but murder.

- Samuel Hoare, a Quaker banker and brother-in-law of Elizabeth Fry, chaired the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline.

- Elizabeth Fry, herself also a devout Quaker, visited the women’s section of Newgate Prison in 1817 and found women and their children crowded together in appalling conditions.

From this initial awakening came a lifetime of service to prison reform inspired by Christian devotion and compassion.

A series of Acts of Parliament followed that improved conditions in prisons, and the treatment and trial of criminal offenders. The Juvenile Offenders Act of 1847 allowed children under the age of 14 to be tried before two magistrates, making the process of trial for children quicker and out of the public glare of the higher courts. Then, between 1854 and 1857, a series of Reformatory and Industrial School Acts replaced prison with specific juvenile institutions. The Education Act of 1876 was the culmination of several measures establishing the principle that all children should receive an elementary education.

In parallel with the law, evangelical reformers were active throughout the century to raise awareness of the special needs of children and to provide care and compassionate action for them.

- The Ragged Schools were founded in the 1840s to provide free education for the poorest of the poor. With Lord Shaftesbury as its President, the movement grew successful providing an education for 300,000 children who, as Charles Dickens noted, were ‘too ragged, wretched, filthy and forlorn to enter any other place.’

- In 1835 Mary Carpenter, daughter of a Unitarian minister, was appalled by the way in which young people learnt criminal behaviour at an early age and founded the Working and Visiting Society to focus on the needs of young offenders.

- From 1851 the London Shoe Black Brigade, established by Lord Shaftesbury and John MacGregor, offered regular employment for children who donned a smart coloured uniform to give them pride and dignity.

- In 1865 General William Booth established the Salvation Army ‘to rescue the fallen, and to find work for the starving unemployed’. By the time of his death in 1912 the Army was at work in 58 nations – everywhere focusing on the needs of the poor.

- In 1866 John Groom set up the Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission to assist the poor street-hawkers of flowers and watercress – later known as John Groom’s Crippleage.

- In 1870 Dr Thomas Barnardo opened his first home for orphans in Stepney Causeway. One evening an 11-year old boy, John Somers (nicknamed 'Carrots') was turned away because the shelter was full. He was found dead two days later from malnutrition and exposure and from then on the home bore the sign ‘No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission’.

- In 1881 two brothers, Edward and Robert de Montjoie Rudolf, went after two boys who had stopped coming to their Sunday School. They found them in a neglected state begging for food from workers at a local gasworks. Their father had died leaving their mother with seven children to look after. It was the start of the Waifs and Strays Society that within 20 years was caring for more than 3,000 street children. Today it is known as the Childrens’ Society.

- Out of the Ragged School movement came another of today’s great Societies – the London City Mission, begun in the home of a young Scotsman, David Naismith, in 1835 - ‘to afford religious instruction to the inhabitants of London and its vicinity, especially to the poor, by means of lay missionaries’. In 1853 a city missionary ‘observed a child under 7 years of age being led away by a policeman, for picking the pocket of a lady… He traced out his mother, who lived in Westminster, and found that this child and his brother, aged 14, were both sent out by her to obtain money how they could, to support her in vice. The elder boy had been often in prison.’

The great Christian reformers of the nineteenth century set a powerful standard for us today. As was London in the nineteenth century, so it is today in many parts of our 21st century world. Children work in virtual slavery; millions never go to school; many fall foul of laws that have no respect for children’s rights and end up in jails or worse. The 83 year-old General William Booth of the Salvation Army gave his final great challenge to a throng of 7,000 Salvationists in the Royal Albert hall three months before his death in 1912.

According to the 1851 census only 20 children under the age of 10 were in British prisons and only one in London. Between the ages of 10 and 15 the number rises to 875 (299 in London).

Decommissioned ships moored to serve as prisons and for those awaiting deportation. Memorably described in the opening scenes of Dicken’s Great Expectations: "The black Hulk lying out a little way from the mud of the shore, like a wicked Noah's ark, cribbed and barred and moored by massive rusty chains, the prison ship seemed to Pip's young eyes to be ironed like the prisoners."

John Garwood - The Million-Peopled City (1853) Chapter 1. Available on the remarkable and extensive website which is worth thorough investigation: http://www.victorianlondon.org/

Quoted in Peter Ackroyd, London the Biography (Chatto & Windus, London 2000) p.600 John Garwood,op.cit.ohn Garwood,op.cit

James Greenwood - The Seven Curses of London (1869), ch.10, found at http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/seven10.htm#gaol

John Garwood, op.cit http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/MOLsite/learning/features_facts/world_city_6.html www.bbc.co.uk/history/society_culture/welfare

John Garwood,op.cit.

Richard Collier, The General Next to God (Collins, Glasgow 1965) p.220

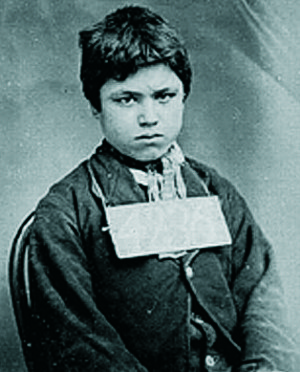

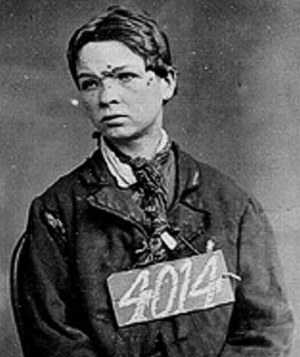

More than 600 photographs and records of Victorian prisoners, who were flogged and imprisoned for offences such as stealing tea or coffee, have been made available online for the first time by The National Archives in Kew and can be viewed at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk . The National Archives has one of the largest archival collections in the world, spanning 1000 years of British history, from the Doomsday Book to newly released government papers. Just Right is grateful for the special assistance given by the Press Office with the preparation of these photographs for reproduction here.